Kaiser Permanente’s Department of Research and Evaluation in Southern California is 1 of 42 health systems selected to participate in a PCORI initiative.

Most stroke patients could be treated at a primary stroke center

Kaiser Permanente research could guide emergency transportation policies to comprehensive stroke centers

By Sue Rochman

Even if emergency personnel were able to use the best stroke assessment tool available, most patients taken directly by ambulance to a comprehensive stroke center could have been treated at a primary stroke center instead, a new Kaiser Permanente study suggests.

The research, published in the Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open, could help inform policies that guide care for stroke patients who are being transported by emergency medical service paramedics.

“Our study suggests only a very small number of patients benefit from being taken by ambulance directly to a comprehensive stroke center, rather than to a primary stroke center,” said the study’s senior author Mai N. Nguyen-Huynh, MD, MAS, a research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research and the Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) regional medical director for primary stroke for The Permanente Medical Group. “This means care may be delayed for those who could be taken to the closest stroke center.”

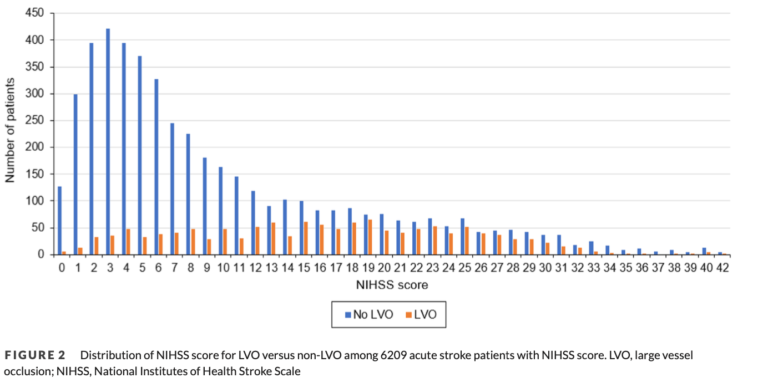

For the study, the researchers hypothesized the transportation decisions emergency personnel would have made if they had evaluated potential stroke patients using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), a 42-point scale that is widely considered the best for assessing stroke severity. This scale is more accurate than the shorter scales emergency personnel have time to use, but it is not perfect. Only neuroimaging tests that can be done at a hospital, such as an angiogram by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), can definitively determine the presence of a large vessel clot.

In the U.S., about 800,000 people have a stroke each year, and someone dies of a stroke every 4 minutes. But not all strokes are the same. Ischemic strokes, which are the most common, occur when a clot blocks a vessel that supplies blood to the brain. Ischemic strokes can be treated with an intravenous clot-busting drug.

A large vessel occlusion is a more severe type of ischemic stroke that occurs when a clot blocks a major artery in the brain. This type of stroke is typically treated with an endovascular thrombectomy. The procedure uses very small catheters that are inserted into the groin or arm and guided to the brain to remove the blood clot. It is typically done within 6 hours of the onset of a stroke, and can only be performed at a thrombectomy-capable center or a comprehensive stroke center. Most people who experience an ischemic stroke are not found to have a large vessel clot on a neuroimaging test.

To investigate how many stroke patients are likely to benefit when emergency personnel assess for a large vessel occlusion in the field, the research team analyzed data on the 13,377 potential stroke patients brought by ambulance to one of the 21 KPNC stroke centers between 7 a.m. and midnight from January 2016 to December 2019. Of the 13,377 patients, 6,089 met the criteria for stroke treatment and had NIHSS score data available. Of these 2,573 had an NIHSS score greater than 10, putting them at higher risk of having a large vessel occlusion.

If emergency personnel had used the NIHSS scale, they would theoretically have transported these patients with a score greater than 10 directly to a comprehensive stroke center. However, the study showed that only 703 of these patients with a high NIHSS scores actually had a large vessel occlusion on neuroimaging. An additional 181 patients who had an NIHSS score of 10 or less also had a large vessel occlusion. Ultimately, only 884, or 6.6% of the 13,377 patients brought in by ambulance for suspected stroke needed treatment at a comprehensive stroke center for a large vessel occlusion.

Some U.S. counties and states have implemented policies that require emergency medical personnel to use a short scale to quickly identify stroke patients most likely to have a large vessel occlusion. These stroke patients are transported to a comprehensive stroke center, even if there is another primary stroke center that is closer. However, not all health care providers support these policies.

“It’s been an ongoing controversy about whether emergency personnel should evaluate stroke patients and determine the level of care they need, or if the evaluation should be done by a neurologist or an emergency department physician at the closest hospital,” said the study’s lead author Jeffrey G. Klingman, MD, chair of chiefs for neurology for The Permanente Medical Group. “The stroke scales emergency personnel use are not able to accurately identify these patients.”

With stroke, time to treatment matters. Hospitals are evaluated on their door-to-needle time—how long it takes for a stroke patient to be given an intravenous clot busting drug after arriving at the hospital. Guidelines recommend a door-to-needle time of 60 minutes or less. A 2017 study by Nguyen-Huynh and Klingman found door-to-needle times average just 34 minutes at all 21 KPNC hospitals. Nineteen of these hospitals are primary stroke centers; 2—in Redwood City and Sacramento—are comprehensive stroke centers.

“The innovative aspect of this study is that it allows us to see that in the best case scenario, using the NIHSS scale and a cutoff of 10, at most 1 in 4 patients taken to a comprehensive stroke center will need an endovascular thrombectomy,” said Nguyen-Huynh. “For the others, if there is a closer hospital, time to treatment with an intravenous clot busting drug is delayed if they are taken to a comprehensive stroke center that is farther away or to one with a slower door-to-needle time.”

The study did not include potential stroke patients who did not arrive by ambulance. About half of all possible stroke patients drive to a hospital, despite ongoing public education campaigns that encourage people who suspect they are having a stroke to call 911.

“I hope our findings help people to see that we need to develop new ways to think about these policies,” said Klingman. “It may be better for hospitals to improve their door-to-needle times and their transfer times for patients who need a comprehensive stroke center than to have policies that require emergency medical personnel to decide where a stroke patient should be treated based on their initial evaluation.”

This research was supported by the TPMG Delivery Science and Applied Research Physician Researcher Program.

Sue Rochman is a senior writer with the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research. This is reprinted from the Division of Research site.