The AMA recognized 4 Permanente Medical Groups for continuing efforts to support physician wellness with 2023 Joy in Medicine™ recognitions.

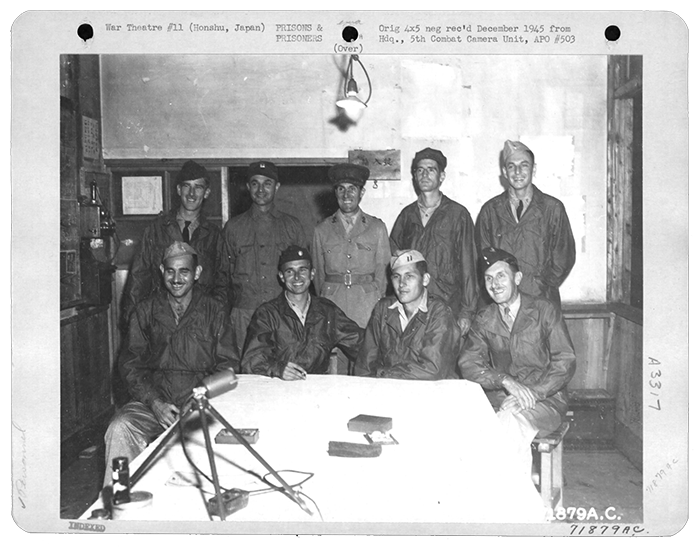

Allied officers who were appointed officers at the Hanawa Prisoner of War Camp #6 in Honshu, Japan. September 1945.

Dan Golenternek, MD – POW physician

Permanente legacy found in service of physicians during WWII

Heritage writer

When we think of Army veterans, we usually think of infantry soldiers who fought on the front lines. But the armed forces also include health care professionals whose medical service exemplifies the highest levels of sacrifice and bravery. Dan Golenternek, MD, endured World War II in just such a manner that serves as a shining example.

The first reveal of his sacrifice emerged when we learned he was a prisoner of war in a short report from the Oakland (Kaiser) Permanente Foundation Hospital in the December 1945 issue of the Alameda-Contra Costa Medical Association Bulletin:

Coffee consumption in the staff dining room rose sharply in October with a daily contingent of colleagues back from the wars to tell their stories and catch up on gossip from the home front. Major Dan Golenternek has gained back 90 pounds of the somewhat more which he lost during three and a half years in Japanese prison camps…

Such weight loss is alarming. What happened?

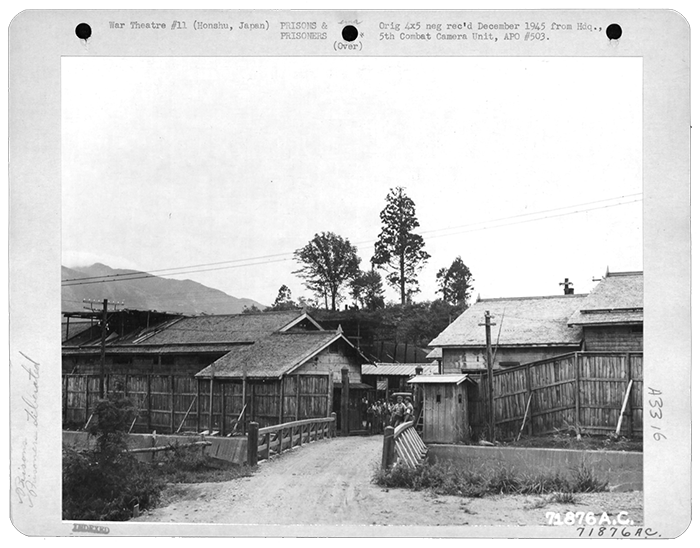

Dr. Golenternek, who’d been training at L.A. County Hospital before enlisting in the Army, was captured by the Japanese Army in April 1942 and imprisoned in the Philippines soon after he’d gone to the South Pacific. Later he was one of two U.S. Medical Corps physicians at the Sendai #6-B prisoner-of-war slave labor camp working at the Mitsubishi Mining Company copper mine in Hanawa, Japan. At liberation, it held 546 POWs: 495 Americans, 50 British, and 1 Australian. The other physician was John Lamy, MD, with a rank of First Lieutenant.

The Sendai camp was established on September 8, 1944, and liberated a year later. It was filled with prisoners (including survivors of the infamous Bataan Death March) shipped from the Philippines to Japan on the “hell ship” Noto Maru. The Noto Maru sailed from Manila on August 27, 1944, transporting 1,035 American POWs to Port Moji, Japan. Dr. Golenternek was one of them.

Army Air Corps Technical Sergeant James T. Murphy, who survived the Sendai camp, recounted the horrific conditions and Dr. Golenternek’s role:

Dr. Golenternek was not given any medicines or medical facilities in his required job of keeping the slave-laborers — the American POWs — fit enough to walk the two miles to and from the mine daily, in their inadequate clothing and shoes, and to perform their 12-hour shifts … By hook and by crook, by sheer innovation … he managed to keep the sickest POWs from going to the mine. He created medical facilities and methods to treat wounds where there were none. He even convinced the Japanese to increase our food rations. All his methods had curative effects, and during that year of 1944-1945, only eight POWs were lost.

Another POW physician, Harry Levitt, MD, recounted earlier experiences with Dr. Golenternek at Bilibid and Rokuroshi Camps in the Philippines:

In Bilibid, Dr. Golenternek was called to care for the Japanese commander, who had an indolent ulcer on his leg that didn’t heal despite three surgical attempts by Japanese doctors. The commander told Dr. Golenternek to operate and cure the ulcer or he would be executed. At first, Golenternek was reluctant to aid the enemy, but reconsidered after realizing his own death was imminent. The ulcer did heal. A reward of extra food, antibiotics and vitamins was secretly provided for the POWs, because the appearance of unyielding brutality had to be maintained by commander.

After the war and brief service at the Permanente Hospital in Oakland, Dr. Golenternek returned to Los Angeles to complete his training in obstetrics and gynecology. He never spoke about his wartime experiences and died in 2004.

Lincoln Cushing is archivist and historian for Kaiser Permanente. This is reprinted from the Kaiser Permanente History Blog. Photos courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.