Kaiser Permanente's report in NEJM AI details insights from a large-scale rollout of ambient AI clinical documentation technology.

Blood pressure patterns in early pregnancy tied to later risk of hypertension

Kaiser Permanente research identifies patterns tied to increased risk of pregnancy-related high blood pressure conditions

By Sue Rochman

Blood pressure patterns seen during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy may offer critical clues to identify the patients most likely to develop high blood pressure complications later in their pregnancies, Kaiser Permanente researchers report.

“Our study shows that a woman with normal blood pressure that increases or shows little or no decline during the first half of pregnancy is at substantially higher risk of developing a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy in the second half of pregnancy,” said lead author Erica P. Gunderson, PhD, MS, MPH, senior research scientist in lifecourse cardiovascular and metabolic research at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research.

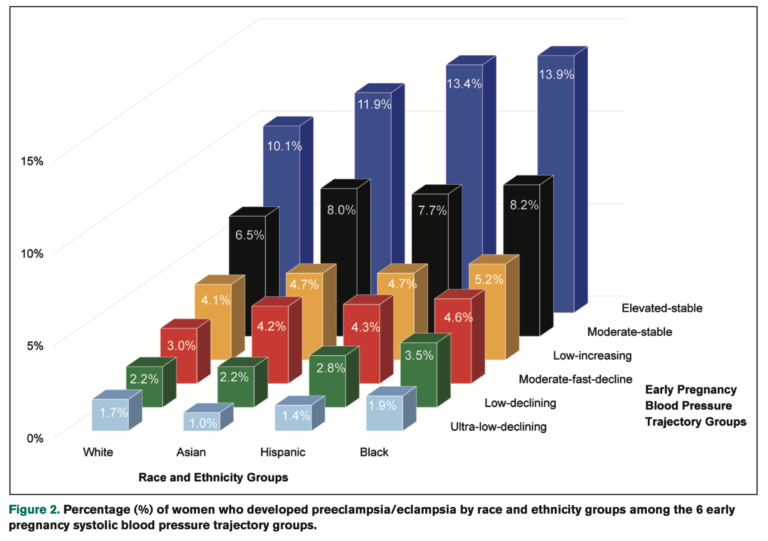

The study, one of the largest and most racially and ethnically diverse of its kind, was published in Hypertension. It included close to 175,000 women with no prior history of high blood pressure or preeclampsia who began receiving prenatal care before their 14th week of pregnancy and gave birth at a Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) hospital between 2009 and 2019. Within the study group, 63,297 patients were white; 44,216 were Asian; 46,289 were Hispanic; and 12,708 were Black.

On average, each woman had her blood pressure measured and recorded at 4 different prenatal care visits during the first half of her pregnancy. An analysis of these consecutive measurements identified 6 distinct blood pressure change patterns; 3 of the patterns were tied to a significantly increased risk of developing a pregnancy-related high blood pressure condition in the second half of pregnancy. The patterns captured almost 80% of the pregnancy disorders, which include preeclampsia (the sudden development of high blood pressure), and eclampsia (preeclampsia plus seizures tied to high blood pressure), and gestational hypertension. In all 6 blood pressure pattern groups, Black women had the highest risk of preeclampsia compared to white women, followed by Hispanic and Asian women.

“Hypertension disorders of pregnancy are one of the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. and they are very difficult to predict and prevent,” said study co-author Mara Greenberg, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist with The Permanente Medical Group. “There have been a lot of studies looking for biomarkers that could predict these hypertensive conditions, but nothing that has proved particularly useful. Blood pressure measurements are readily available in the medical record and could be a useful tool if we can show blood pressure patterns can predict who will develop these conditions.”

From low risk to high risk

Hypertension-related maternal mortality in the U.S. affects 2.1 per 100,000 live births, with Black women nearly 4 times as likely as white women to die from a hypertension-related condition during pregnancy. Patients with chronic hypertension, overweight or obesity, diabetes, a previous pregnancy with preeclampsia, or who smoke are known to be at higher risk for hypertension-related problems during pregnancy and were excluded from the study. The new study identified pregnant patients who are considered to be low risk but then go on to develop hypertension-related complications.

“There is a normal physiological blood pressure response to pregnancy which includes a dip in your blood pressure in the second trimester,” said Greenberg. This occurs because as the placenta starts to develop in the first and second trimester of pregnancy, it produces hormones that cause the blood vessels to be more relaxed in order to bring more blood to the uterus and the fetus. “When patients don’t experience this, they might have something going on in their body that could put them at increased risk of developing a high blood pressure condition later in pregnancy,” Greenberg added.

Our study shows that a woman with normal blood pressure that increases or shows little or no decline during the first half of pregnancy is at substantially higher risk of developing a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy in the second half of pregnancy.

— Erica P. Gunderson, PhD, MS, MPH

In the study, 8,342 patients developed preeclampsia and 8,767 developed gestational hypertension. Overall, the patients diagnosed with high blood pressure-related complications were more likely to be younger, Black or Hispanic, have overweight or obesity before pregnancy, and not have previously given birth. They also were more likely to gain more weight during their pregnancy, require a cesarean birth, or have a baby that was smaller than average, born preterm, admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit, or die after 22 weeks of pregnancy.

The statistical association between the blood pressure patterns the researchers identified and the later development of a high blood pressure pregnancy condition was further improved when information about the patient’s race, ethnicity, pre-pregnancy body-mass index (BMI), diabetes, and socioeconomic status was included.

“The next step is to evaluate how well these blood pressure patterns predict later hypertensive complications in order to target individuals for early prevention,” said Gunderson, “and we are working on that right now.”

Pre-term delivery is currently the primary way doctors manage complications that develop due to pregnancy-related high blood pressure. Earlier identification of high-risk women creates the potential for introducing new interventions that could improve outcomes for mothers and babies.

“There are many factors that contribute to a person developing high blood pressure during pregnancy, and many are related to a person’s underlying health as they come into pregnancy,” said Greenberg. “For patients, this study reinforces that you should have your blood pressure checked several times during the first half of your pregnancy — even if you start pregnancy with normal blood pressure — because what we learn from those measurements can be useful.”

Sue Rochman is a senior writer with the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research. This is reprinted from the Division of Research site.